An interview

You spent 10 years travelling the world – essentially homeless. You wrote journalism to support yourself. What affect did that have on your work?

Directly, not much, in that my work is not about globalisation or the media. Although I did spend a lot of time thinking about those issues. I was very young when I realised that travel was essentially quite selfish. I was in Zimbabwe – I was 19 – and I was on a bus and a man asked me why I was travelling. I was shocked by the question – travel had always seemed to me self-evidently important, and here’s this guy who has never been further than the neighbouring village! Some time later I realised that that the “importance” of travel was a cultural construct and that the only reason to travel was to find myself.

And did you?

Yes, I feel like a grown up now. But it took a whole lot of sex, drugs and rock n roll to get there.

Care to share?

Oh, too many stories. You’ll have to wait for my autobiography.

Travel must have impacted your work in some way though.

Chora Church, Istanbul – St Paul, 14th Century

Of course. For starters, it allowed me to see art from all over the world, and not just the great works of the Western canon. While living in Turkey, for instance, I discovered Byzantine art, which had a profound impact on me. Most importantly travel gave me a truly global outlook. It made me realise that people all over the world have their own traditions and that what we consider “important” in art historical terms is often just about who happens to be rich and powerful at the time.

You were accepted to art school but chose art history and curatorship instead. Then abandoned that and became a travel writer…

I don’t know why I didn’t go to art school. Actually, I do: I was very arrogant. I thought I didn’t need someone to teach me how to paint or draw, but post-structuralism… well, that was for smart people! During my university years, I drifted away from painting. Academia killed the joy of art for me. I remember one day I was talking to my [thesis] supervisor, looking at his new book about a late 17th-Century French academician. I was like, “Ah, I don’t want to say this, but this stuff is awful.” And he’s like, “Oh, yes! He’s a terrible artist.” I realised at that point that being an academic and loving art were two different things. How could I write about art that didn’t move me?

What was your thesis about?

Ugh. Depictions of Aboriginal people in early Australian colonial art, Kant and the Sublime. Post-colonialism was all anyone was doing in Australia in the 90s. I was considering a PhD but I found the world of curatorship and academia too dull, like joining a monastery. Luckily, I discovered a talent for writing – I had edited the university newspaper and was heavily into the punk and indie scene. Eventually I worked for a newspaper in Sydney as a rock critic. I enjoyed it but, ultimately, it was not very satisfying. When I got an offer to write my first book I quit and started my vagabond life.

So can I ask about your techniques? Why styrofoam? How did you come to work with it?

Rudolf Stingel – Untitled, 2000

In about 2008 I had a kind of nervous breakdown. For two years I did pretty much nothing but watch TV and jerk off. One day I saw one of those Rudolf Stingel styrofoam pieces – the ones where he walks on the blocks with his shoes soaked in solvent, like snow tracks. I don’t know why but it blew my mind. I had been out of the art loop for some time and it rekindled my love. The work was so elegant, so witty and yet so melancholy. I started carrying a print of it with me. I was showing it to people, totally unprompted. Everyone must have thought that I’d really lost it! At the same time I started seeing a therapist. I was diagnosed with major depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. I went on medication and it was like a switch clicked in my brain. It was incredible – I immediately wrote a book and started madly experimenting with art.

You started working with styrofoam?

Not immediately. In my late teens I had done text-based works – painted letters cut from wood, a bit like Doug Aitken. I thought that styrofoam would be an easier material to cut. Plus, it was just sitting around on the street. Then, inspired by the Stingel piece, I started melting it, burning it, doing all sorts of experiments. It took almost a decade to work out how to use it properly and make pieces that were up to my technical standard. It was an oddly arbitrary decision to work in this medium. But it was a strange twisting path, and ultimately it felt right.

What did you learn in that time of experimentation?

It’s an extraordinary material. There’s something almost biological about it. It responds to heat, to cold, to different solvents in different ways. There are so many different densities. The combinations are endless. When I’m in the factory buying slabs, I feel like Michelangelo selecting the right marble. So exciting! You can create these huge blobs by melting it in solvents and then watch them run down and sink into the slab – imagine Pollock in extreme slow motion. It can get hard or soft depending on the temperature, but it’s never really a solid. It can always be reanimated with heat, like glass. My husband doesn’t like it because he says that it looks like old cum. [Laughs]. But that’s fine. I don’t mind Freudian interpretations of the work. A lot of people are hesitant to say it looks like those things – poo, guts, snot or whatever – but I love it!

The process is almost analogous to cooking, or “cooking” drugs.

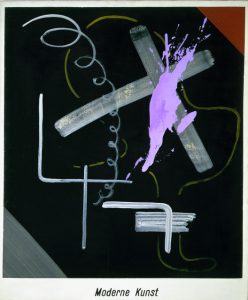

Sigmar Polke – Meteor II, 1988

Very much. I’m a big foodie, very into molecular gastronomy. In many ways I feel like what is happening in food right now is more interesting than what is happening in art. Indeed, what’s happening in drugs is more interesting too. [Laughs]. When I was a kid, one of our favourite games was “making potions”. My sister and I would get all sorts of things from the garden, the kitchen cupboard, and mix them together – detergent, flour, dog shit, whatever. It was just for the fun of putting things together that shouldn’t be together. We were like witches! Very transgressive. At the same time we were raised in a very Catholic household, so that notion of the transubstantiation was there, every Sunday. The idea that a thing can magically become another thing is one that never really left me.

Sigmar Polke was fascinated by alchemy and decay…

Like Polke, chance plays a big part in my work. If I leave it sitting in the sun and come back in an hour, it’s a different painting. The composition is left up to forces outside of my control. I find that very exciting. It’s as if the work were an antenna or a medium between me and something else.

Polke was a big traveller, too.

Indeed. He was aware of all these alternative perspectives, these local traditions and histories, “regional” styles and “parochial” modernisms. He even spent time in Tasmania.

Long before there was a famous contemporary art museum there.

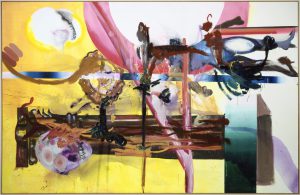

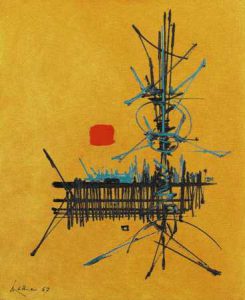

Stanislaus Rapotec – Untitled, 1964

Yes! Like Polke I am drawn to these hidden histories, to artists outside the canon, people who are hard to classify or those considered on the fringes of major movements. For instance, I love all the Art Informel artists who have gone out of fashion. Many were stars in their day and are now totally forgotten. I grew up with paintings like that – heavy, impasto abstractions sitting in dark corridors at my university, in the library, at government offices. Dusty, forgotten and mysterious. I wondered who these people were, these victims of time and fashion. I marvelled at the cruel arbitrariness of history.

It’s a big part of the Australian psyche – this awareness of being on the margins – isn’t it?

Oh yes. It’s arguably our defining national neurosis. We are quite accustomed to being ignored.

So why painting? Why not some other form?

Jackson Pollock – Totem Lesson 2, 1945

Why anything? In an era of infinite possibility, how do you make any choice? In the post-internet age that might be the greatest question of all. Painting is one of the ways we construct and record history. It allows you to speak across the ages. Painting is a metaphor for time. Painting was my first love. I grew up visiting the National Gallery in Canberra. I would spend hours looking at Pollock, De Kooning, Rothko and all the rest. In some ways they’re quite critically unfashionable now. Their silly little modernist fights seem hilarious in retrospect. Did you know that Morton Feldman, the composer, stopped talking to Philip Guston after he turned to figuration?

Ha! Like Dylan going electric – “Judas!”

[Laughter] Exactly! Ridiculous. Despite this, I still find the gauche sincerity of modernism infinitely preferable to what we have now. Modernism stood for something bigger than yourself. Like, you could put on your colours and go into battle for the honour of your house: Cubism! Surrealism! Minimalism! What’s our big idea now? That we’re all victims and should retreat to petty tribalism? Identity politics depresses me because it represents precisely the kind of parochialism I hated in Australia. When I was growing up, everything was about “what it means to be Australian”. But I didn’t give a shit about being Australian! I wanted to know what it meant to be human! I look at Kara Walker and I can’t help but think: wouldn’t I better off reading a history textbook? But when I look at a painting by some obscure Australian cubist I see an artefact that exists only for itself – removed from the world and the petty bullshit of humanity. I find that thrilling and liberating, a vision of utopia, no matter how naive or ultimately unsuccessful.

OK, but isn’t simply making marks on a canvas kid of self-

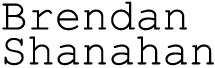

Philip Guston – Bad Habits, 1970

indulgent?

Sure, but art is self-indulgent. Are you telling me that, like, Tania Bruguera, Sam Durant or Ai WeiWei are “changing the world”? If you wanna change the world, become a teacher at a shitty high school, not a wealthy installation artist, preaching to the converted. That said: what to paint is a very ancient question, and gestural abstraction seemed especially futile. Firstly, where do you start? Why make one mark and not another? Should I invent a system? I came upon the technique of melting the styrofoam because it couldn’t be changed. If you splashed it, that was it – you had to accept the result or destroy it. So it was as if the gesture was frozen in time, that the gesture itself became almost arbitrary. The real subject of the painting was the enormous effort it took to “freeze” this moment in time.

That’s interesting. Sterling Ruby said something very similar about wanting to “freeze a gesture” when he was making his stalagmite sculptures.

Lynda Benglis – Totem, 1971 (destroyed)

Well, I think Lynda Benglis beat him to it. Indeed, there was an essay in the 1970s about her work titled The Frozen Gesture. No matter – I’m a big fan of both. I especially love those Ruby sculptures. They’re painterly, shiny and delicious, but also very sinister. There’s something dirty and biological about them that I love.

Sterling Ruby – Monument Stalagmite/Headbanger, 2008

Your work is, to at least some extent, “painting about painting”. Do you see yourself as a conceptual painter?

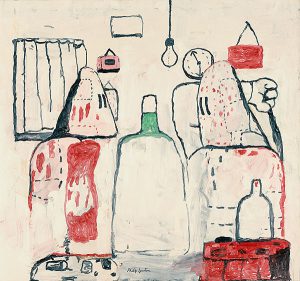

No. Aside from anything else, I like making pretty paintings too much! But if I want to engage in an historical conversation with painting I cannot ignore the strategies of post-modern painting. I have to deal with them, if only to negotiate some kind of truce. For example, we mentioned Polke earlier and I think a lot about the Germans – Richter, Polke, Kippenberger and co. Their strategies were essentially conceptual – jokey, ironic, affectless – and in direct opposition to the grand claims and turgid emotions of modernism, specifically expressionism. Polke’s painting Moderne Kunst is the archetype. It says: “Look how pointless ‘art’ is.” I think it’s brilliant, but it’s shocking because it’s so caustic. It’s not cynical, necessarily, but it’s angry. I see someone who felt betrayed by the promises of modernism – someone who escaped East Germany and all that Marxist shit only to be confronted by the emptiness of capitalism, of which abstract art, it has to be said, was a part. It’s a brilliant, bold gesture. But by the time we get to someone like Albert Oehlen the whole thing just feels suffocating, nihilistic almost. I read a recent interview with him where he says something like, “Art does not move me. I just like ideas.” He even says that Francis Bacon doesn’t make him feel anything. For real? Who can look at Bacon and feel nothing?

A German.

[Laughter]. Everything’s better with Bacon!

[Laughter]

Sigmar Polke – Moderne Kunst, 1968

But, seriously: the point is that a lack of feeling betrays a failure of imagination. And where did this weird suspicion of feeling in art come from anyway? Also, we need to ask whether the utopian ambitions of modernism can be so easily dismissed, whether infinite subjectivity will lead us to a place that’s any better than modernism’s striving for objectivity. Look at the internet: we’re trapped in a mirror maze. Ideas and imagery are ripped apart and digested as quickly as they’re produced. There are no unmediated experiences, and it’s killing us.

Did you choose to interview yourself as some sort of joke about the self-reflexivity of the post-internet world?

Not really. I have a life-long habit of interviewing myself – like, I would sit on the toilet pretending I’m on Letterman or something. It’s all free association but it’s a good way of refining and clarifying my ideas. I was a champion high school debater, so I’m very good at playing devil’s advocate. Too good – my self-doubt can be crippling. I know a lot of curators from my university days, so I guess I could have asked one to interview me, but that felt awkward. In the end I decided that as a journalist and curator no one could be better qualified!

Then I guess all those formulaic articles you wrote weren’t for nothing.

Trust me – they were among the less humiliating things I’ve done for money.

Your work is steeped in art historical references. Does it run the risk of becoming pastiche?

Albert Oehlen – Evilution, 2002

It sort of is pastiche. Imagine me as a kind of DJ, remixing the record crates of history. I love how a DJ can take some tired, corny cliche of a song and make it fresh. In that sense I’m probably less interested in doing something “new” with painting, in formal terms than I’m interested in the way in which history is constructed. Like: what if in the distant future George Mathieu is considered a great genius and Pollock is a forgotten stylist? Or: imagine an alternate dimension in which Pollock is 95 and still just a weird provincial surrealist. What would that work look like? If I could be said to have a view of history then it might be described as Borgesian: history as an infinite house full of endless corridors, strange dead ends and forgotten doors.

Does being Australian and having been exposed to so many other cultures make you more aware of the possibility of “alternative histories”?

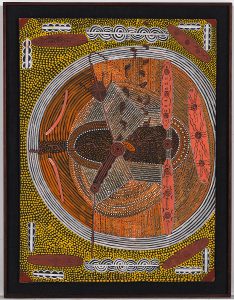

Absolutely. In the Western tradition, history is a paradox because it never really exists – as soon as we become aware of the passing of time, it’s gone. This is very different to, say, the Aboriginal notion of history, which is not really “history” at all. Their radically different sense of time means that all possible events are happening simultaneously – the future too! History is not a road we’re racing down; it’s an ocean we’re swimming in.

George Mathieu – Untitled, 1967

I wonder sometimes whether, because of the internet, we are shifting to that “Aboriginal” way of thinking: just as there has been a “flattening” of aesthetics globally, there has also been a “flattening” of history.

Yes. We live in an atemporal world. An artist today is free to draw on any historical period, any theme, any culture. They have access to almost everything. It’s almost more pertinent to ask why an artist chose not to work in a particular style.

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri – Love Story, 1972

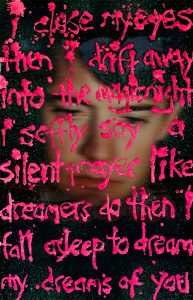

How do your text paintings fit into your thinking about history?

They don’t. Technically, they’re the same process, but they’re different. The word paintings started because one of the symptoms of my OCD was that certain phrases would get stuck in my head: song lyrics, advertisements, fragments of conversation… whatever. I would find myself compelled to repeat them constantly, sometimes out loud. It became embarrassing. I wondered where they came from. I started to think of them as coded messages or even prayers, incantations that might protect me from some unseen evil. Also I was becoming dissatisfied with pure abstraction, but I didn’t know what subject to paint. One day I realised I should use these phrases because they clearly had some meaning to me, even if I didn’t know what it was. Plus, the text was a way of doing a painting while not having to worry about formal properties, while still having formal properties that are very appealing. It was a perfect solution.

So why Roy Orbison’s In Dreams? Why did those lyrics stick with you?

Blue Velvet (film still), 1986

I can’t say for certain, but whenever I developed one of these fixations my psychiatrist would ask me to examine my associations. At the time I kept thinking about the scene in Blue Velvet where Dennis Hopper’s character, Frank, repeats the lyrics into Kyle MacLachlan character’s face. It is terrifying. But why? In Blue Velvet, Frank is the embodiment of pure evil. MacLachlan’s character, Jeffrey, on the other hand, is trying his best to be good. Roy Orbison is also a very popular figure in Australia. Even at his lowest ebb, when he was totally forgotten in the US, Australians still greatly loved him.

An ignored artist who found a niche in an ignored country.

Exactly! My father always had a Roy Orbison tape in the car that we would listen to on family road trips. Roy was always a part of my life and I associate him with my dad.

That’s interesting because there is also a suggestion of Frank as both a perverse father figure and lover to Jeffrey.

Yes, although my father huffs less nitrous than Frank.

[Laughter]

Where was I? Oh yes. Anyway, in that scene Frank seems to be telling Jeffrey that, although he might deny it, he is very much like him – evil walks with Jeffrey “in dreams”. In fact, in the same scene, Frank is very explicit: “You’re like me,” he says. In this moment the film’s central thesis is laid bare: evil is the natural state of man. It’s a terrifying proposition. So what is it that walks with me in dreams? Perhaps it is the gnawing suspicion that we live in a universe ruled by cruelty and chaos and that goodness and hope are doomed.

So it’s not a paean to unfulfilled gay love?

Can you believe that hadn’t even occurred to me until you mentioned it just now? Proof that my technique works!

You should call your shrink and ask for a refund.

[Laughter]

So, you seem to have two major themes, one which we might term formal – engaged with art history and painterly concerns – and one that we might call moral or psychological, an identity project of sorts. Why the dichotomy?

I have always felt that there are two quite distinct halves to my personality. On one hand there is the extroverted thinker: the polymath, prankster and iconoclast. Then there is the feeling introvert, the sincere little boy who is very easily hurt. I never quite know which one is going to show up.

Why do you feel like this?

Possibly it has something to do with my sexuality. Gay people are forced to divide their lives into public and private personas, far more than most people. But I think it’s important not to think of one of these personas as being more “authentic” than the other. They exist parallel but they are also manifestations of something else.

Or, is it that this “third” persona is actually the relationship between the other two?

Exactly. I think if my art has one ultimate aim then perhaps it is to somehow resolve these two halves, or at least give them a space for an uneasy truce, to investigate the nature of their relationship and come to some resolution, some synthesis.

How will you know when you do?

I have no idea. I guess I’ll just keep painting until I find out.

Thanks for your time.

A pleasure for us both.